Independence and Identity of Modern Hellenic Nation-States and Ethno-States

Αύξηση

There was undeniably a strong sense of shared national and cultural identity among the Greeks. Yet, when looking at the history of ancient Greece, one is struck by the disconnect between the pervasive rhetoric of Pan-Hellenic unity and the political reality of fragmented city-states locked in brutal wars—fought fiercely in the name of absolute independence to preserve their unique identities, the most priceless treasure for any tribe.

The polis demanded total loyalty from its citizens, which often meant little hesitation in annihilating other Greeks if it served the immediate interests of the city. Moreover, it is often difficult to gauge to what extent patriotic sentiment genuinely sustained the resistance and resilience of the Greek states, versus serving as eloquent rationalizations for narrow political interests—such as Athens’ ambitions or Sparta’s desire to avoid domination by any foreign, internal, or external power. Indeed, Herodotus reports that the city of Phocis opportunistically sided with the allies only because its traditional enemy, Thessaly, had allied with the Persians. It was common at the time for individual politicians and city governments to collaborate with the Persians, with corruption always representing the true Achilles’ heel of democracies, especially those among unequal peers.

In fact, the city of Delphi came under Persian influence (medizing). In short, as often recurs in history, broader ethnic and civilizational interests were overridden by selfish political agendas.

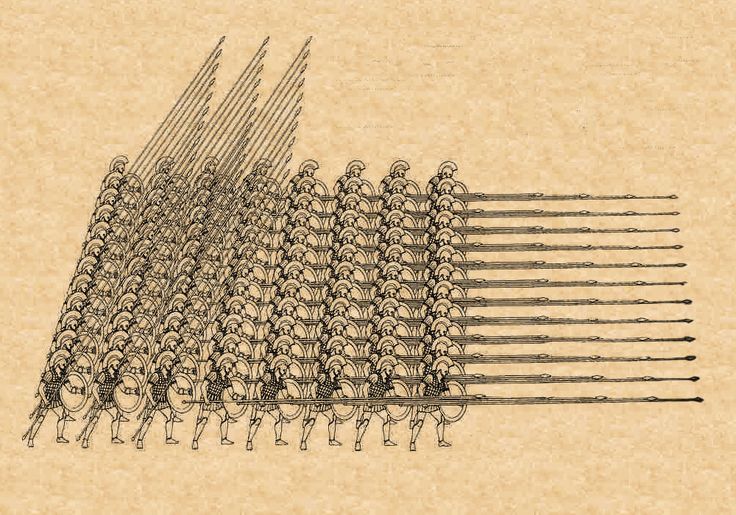

The Hoplite Phalanx

During the Persian Wars, the Greek allies certainly achieved enough unity to ultimately repel the invaders. Still, it is striking how fragile that unity was—and how exceptional such unity was in the broader sweep of Greek history. The “Greeks,” who identified simply as such, ultimately included only around a dozen mainland cities in the alliance; the rest remained neutral or at best collaborated.

Less talked about than the individual polis, the Greeks had a venerable tradition of federalism in the form of leagues of city-states. These leagues typically combined shared temples, a common council, arbitration, military alliances, and coinage, with varying degrees of central authority. Such leagues were a common political feature across regions like Arcadia, Boeotia, Crete, and Ionia. Both Athens and Sparta, each in their own history, led military alliances as hegemonic city-states, serving as the primary unifying force among smaller allies.

These leagues projected the defining features of family religion beyond individual cities into something like a commonwealth: shared blood and gods sealed city alliances, including shared sacred sanctuaries—much like family and polis, which were sacred and secure spaces.

However, these leagues were not true federal states or sovereign federations, but coalitions of city-states, each with its own army jealous of its civic sovereignty. This confederation never had the solidity of a polis. Their effectiveness fluctuated as the need for unity—usually to achieve military scale—tensioned with the centrifugal desire for autonomy by each city. Practically, a league usually functioned well only under the leadership of a dominant city, or at most, under two cities that had an underlying power-sharing agreement. Revolts and subjugations of subordinate cities were common. Greek leagues never expanded beyond their regions and unsurprisingly fell to much larger powers—Macedonia, then drawn into the Western Roman Empire, and later ravaged by barbarians from the East. The fragility of ancient Greek leagues is not unlike the confused confederations of states that have sporadically appeared throughout history, even to today.

Why Never a United Greek Nation-State?

Plato and Isocrates made concrete proposals for Greek unity against the barbarians, but these efforts failed due to the sheer impracticality of federalism prior to the expansion of the Roman Instrumentum Regni. As Montesquieu later observed, in the pre-modern world large-scale political unity was possible only for monarchies, not republics.

External threats were perhaps the strongest drivers of Greek unity. Before the Persian conquest, the twelve Ionian cities of Asia Minor were united in a league that eventually dissolved for classic reasons of local identity, customs, and religion.

These Ionian descendants gathered to worship Poseidon, compete in sports, and hold council in a common sanctuary known as the Panionion. During their brief independence caught between Lydia and Persia, the philosopher Thales of Miletus, famed for his contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and engineering, proposed that the twelve affinity cities form a true political federation with a single governing council seated in Teos (chosen for its central location), with other cities considered effectively as districts.

However, Ionia lacked a dominant city to naturally lead, like Athens or Sparta on the mainland. Another unfulfilled proposal was that, instead of accepting Persian dominance, the Ionians pool resources to sail to Sardinia and found a single powerful mercantile city for all Ionians—an independent state.

Herodotus notes that Persians often lamented Greek disunity. A Persian governor even forced conquered states to bring their disputes to arbitration rather than engaging in mutual pillaging. Mardonius, a chief Persian general during the second invasion, was astonished by the Greeks’ penchant for internal strife and reportedly said, “Since they all speak the same language, the Greeks should send heralds and messengers to resolve their disputes, as anything is preferable to conflict among themselves.”

Herodotus lamented Greek disunity, using the term *stasis*—typically reserved for civil conflicts within cities—to describe inter-tribal strife. He famously said that internal dissent is worse than united war just as war is worse than peace. His expression suggests that Greek ethnic unity should have been the natural condition; failing to achieve this would lead to fragmentation and ruin—“a flame that burns at both ends,” a monumental but fleeting light, turning decay into a tragic, beautiful poetry of war echoed through the millennia.

Unity During the Persian Wars

In practice, Greek unity during the Persian Wars was fragile. In the first invasion (492–490 BCE), Persia secured Thrace, Macedonia, and minor islands, but Athens alone triumphed at Marathon. During the second invasion (480–479 BCE), Xerxes undertook monumental efforts—including digging a canal through Mount Athos and deploying around 200,000 soldiers and 600 warships. The resistant Greek states formed an alliance calling themselves “Greeks,” holding a congress of 70 representatives at Corinth but lacking a centralized government. These states represented only about one-tenth of the 700 Greek cities on the mainland. This alliance assumed supreme authority over the nation and vowed to punish traitors.

Sparta proposed depopulating collaborationist cities and resettling them with Ionian refugees from Asia Minor. Athens opposed Spartan interference and the forced evacuation of Asian cities, effectively rejecting ethnic cleansing.

Sparta held supreme command on land, Athens at sea. Yet this “Greek League” was a rebellious alliance, not an actual state; ultimate survival depended on the uneasy cooperation of Athens and Sparta, two enduring rivals.

Athens, in Attica and closer to Persian control, was mercilessly sacked. Sparta, in the Peloponnesus, aimed to delay battles until the Persians reached southward, even contemplating abandoning Athens to defend just the Isthmus.

Both cities had to show leniency toward each other: Athenians refused to compromise with Persia despite incursions, while Spartans fought heroically at Thermopylae before Persian invasion threatened Laconia, whose fall would doom the entire Peloponnesus.

The Limits of Political Interests Over Ethnic Unity

The tension between political interests and ethnic identity is evident in the case of Syracuse. The Greek allies sent envoys throughout the Greek world—in Sicily, Corsica, and Crete—seeking alliance against Persia, aiming to unite all Greeks in common cause against the imminent threat.

That same year, a largely Athenian fleet defeated the Persians at the naval Battle of Salamis, complementing King Leonidas’ heroic stand at Thermopylae.

In 479 BCE, Athenians and Spartans together won a decisive land battle at Plataea, preserving Greek sovereignty and identity and laying the foundation for Athens’ Golden Age of power and philosophy, and Sparta’s martial legacy.

The Greeks triumphed through a winning combination of civic freedom and solidarity, embodied in the alliance of Athens and Sparta.

Herodotus’ tales poignantly commemorate the fragility and valor of Greek unity—whether in the mass Athenian evacuation to avoid slaughter, or the courageous Spartan sacrifice at Thermopylae, both exemplify unity and sacrifice in arms against subjugation.

Rethinking Western Identity and Freedom

Reducing Western identity merely to “democratic values” among unequal parties is absurd when considering our long history—from tribal hunter-gatherers and “barbarians,” through the Roman Empire, feudal Middle Ages, Enlightenment absolutism, to modern authoritarian experiments. For neoconservatives, “Western civilization” is not synonymous with “democratic imperialism” or “human rights,” nor with imposing a single ideology worldwide. Certainly, the pursuit of freedom is central to Western civilization; yet the preservation of identity remains immutable. The Greek conception of freedom was fundamentally “illiberal,” ethnocentric, and virile. For Herodotus, Sparta as a military aristocracy was as “free” as democratic Athens because Spartans adhered to a holistic government. Athens was dynamic, powerful, and culturally vibrant but its democratic excesses frequently bred unrest. Greek freedom was essentially ethno-political: civic life meant defending simple “values” for their own sake, not imposing them on outsiders. Communal life was participation in and belonging to an organic community defined by blood ties and shared veneration of the Gods.

The only unchangeable fact remains and unaltered, despite all the courage in this world, that the Greek political systems failed and never took flight again.