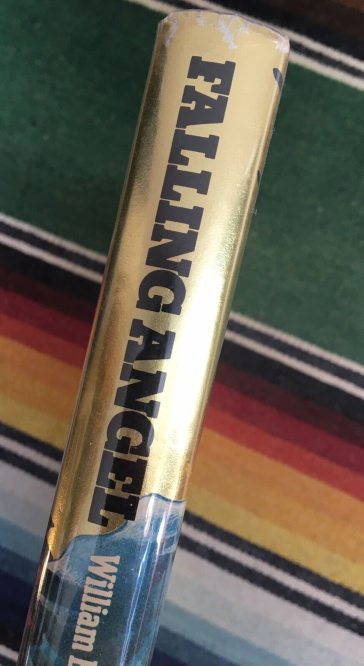

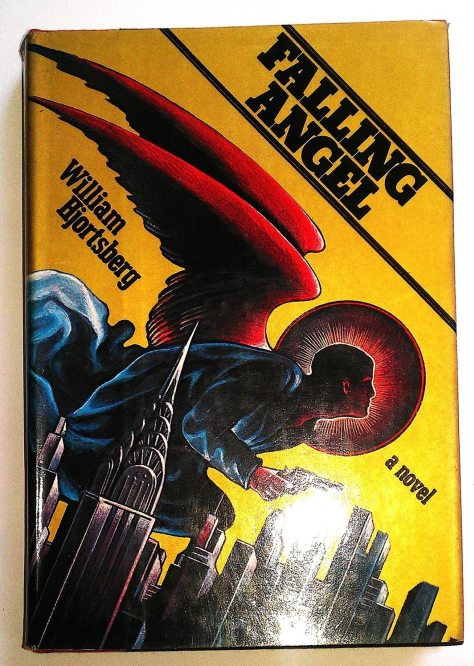

When The Noir Meets A Metaphysical Nightmare : Falling Angel by William Hjortsberg

In the shadowy underbelly of 1950s New York, where jazz clubs pulse like hidden hearts and the air reeks of cigarette smoke and desperation…

William Hjortsberg’s Falling Angel (1978) drops you into a hardboiled detective yarn that’s equal parts Raymond Chandler grit and Lovecraftian nightmare. Our protagonist, Harry Angel—a wisecracking PI with a fedora tilted just right and a moral compass that’s more suggestion than law—gets hired by the enigmatic Louis Cyphre (yeah, say it out loud) to track down a missing crooner named Johnny Favorite. What starts as a routine missing-persons gig spirals into a voodoo-laced descent through Harlem’s occult undercurrents, chicken sacrifices, and soul-shattering revelations that blur the line between the mortal coil and eternal damnation.

Hjortsberg’s prose is a masterclass in noir cool: sharp, rhythmic, and dripping with atmosphere. Sentences hit like bourbon shots—smooth but with a burn that lingers. Harry’s voice narrates with that classic gumshoe cynicism, cracking wise about dames and danger while the supernatural creeps in like fog off the Hudson. It’s not just horror; it’s a genre mashup that feels fresh even decades later, blending pulp detective tropes with Satanic chills without ever feeling forced. The twists? Oh, they’re devilish, building to a finale that’ll have you flipping back pages to see how you missed the signs. If Angel Heart (the 1987 film adaptation with Mickey Rourke and Robert De Niro) hooked you, the book amps up the psychological dread, making the movie feel like a glossy postcard from hell.

This isn’t your grandma’s mystery—it’s raw, unflinching, and unapologetically dark, with themes of identity, fate, and the cost of deals gone sour. Hjortsberg nails the era’s vibe, from bebop beats to racial tensions, all while weaving in occult lore that’s researched enough to feel authentic but wild enough to terrify. If you’re into books that grab you by the collar and drag you through the abyss, Falling Angel is a must-read. It’s the kind of novel that lingers like a bad dream, proving that sometimes the scariest monsters are the ones staring back from the mirror.

William Hjortsberg’s 1978 novel Falling Angel and Alan Parker’s 1987 film Angel Heart share the same dark heart but carve distinct paths through their mediums. The novel roots itself in 1959 New York, painting a noir-soaked world of jazz dives, Harlem’s occult underbelly, and a gritty urban pulse. Hjortsberg’s prose is sharp, rhythmic, and steeped in period details—cigarette haze, bebop riffs, racial undercurrents—making the supernatural creep in like a slow poison. Harry Angel, a cynical PI, hunts for missing crooner Johnny Favorite at the behest of the sinister Louis Cyphre, and the investigation unfolds as a meticulous, slow-burn mystery. The book lingers on secondary characters like Madame Zora and Toots Sweet, grounding the horror in detective legwork. Clues pile up through interviews and stakeouts, leading to a devastating twist—that Harry is Johnny, damned by a deal with the devil—delivered with noir fatalism. It’s a psychological gut-punch, subtle yet shattering, with an ambiguous, bleak ending.

The film, while also set in 1959, stretches the story to New Orleans, adding a sultry Southern Gothic vibe absent from the book. Parker’s visuals—shadowy lighting, spinning fans, bloody rituals—lean into surreal horror, trading the novel’s grounded grit for cinematic dread. The plot is streamlined, cutting minor characters and accelerating the pace with early supernatural hints like dream sequences and mirror imagery. New scenes, like a graphic voodoo ritual and Toots Sweet’s murder, amp up the shock value.

Mickey Rourke’s Harry is grubbier, more pathetic than the book’s cool PI, while Robert De Niro’s Cyphre is overtly menacing, his demonic nature less veiled. The film adds a steamy, controversial sex scene between Harry and Epiphany (Lisa Bonet), who’s more sensual than her less sexualized, culturally rooted book counterpart. The twist is preserved but less subtle, with flashbacks and symbols like elevators spelling out Harry’s damnation more explicitly, ending with a haunting descent to hell.

The book balances noir cynicism with existential dread, using the occult as a metaphor for guilt and fate, while the film prioritizes visual horror and religious imagery—crosses, churches—for a more immediate, less introspective scare. The novel’s depth comes from Harry’s voice and detailed investigation; the movie’s power lies in its feverish atmosphere and Rourke’s raw performance. Both nail the story’s core, but the book is a detective’s notebook, the film a nightmare on celluloid.

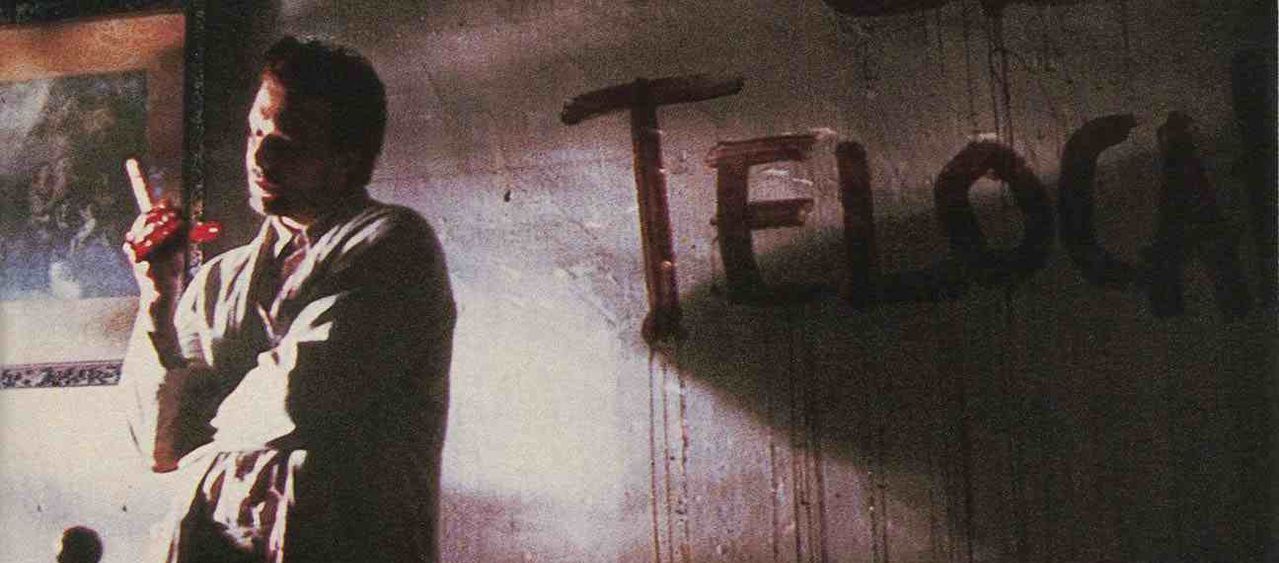

In Angel Heart, the word “teloca” appears scratched in a Coney Island bathroom stall, a cryptic clue Harry finds while chasing Johnny Favorite’s trail. It’s a film-specific addition, not in the novel, and likely an anagram for “Calote” or a nod to “Locate,” pointing Harry toward the truth of his own identity. Some fans tie it to “Telos” (Greek for “end”), but it’s mainly a plot device, amplifying the film’s eerie tone and Cyphre’s manipulative game. It underscores the theme of hidden truths, a visual hint that Harry is both hunter and prey.

##########

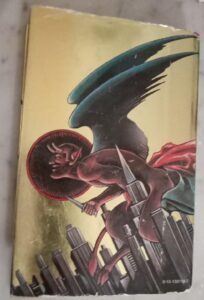

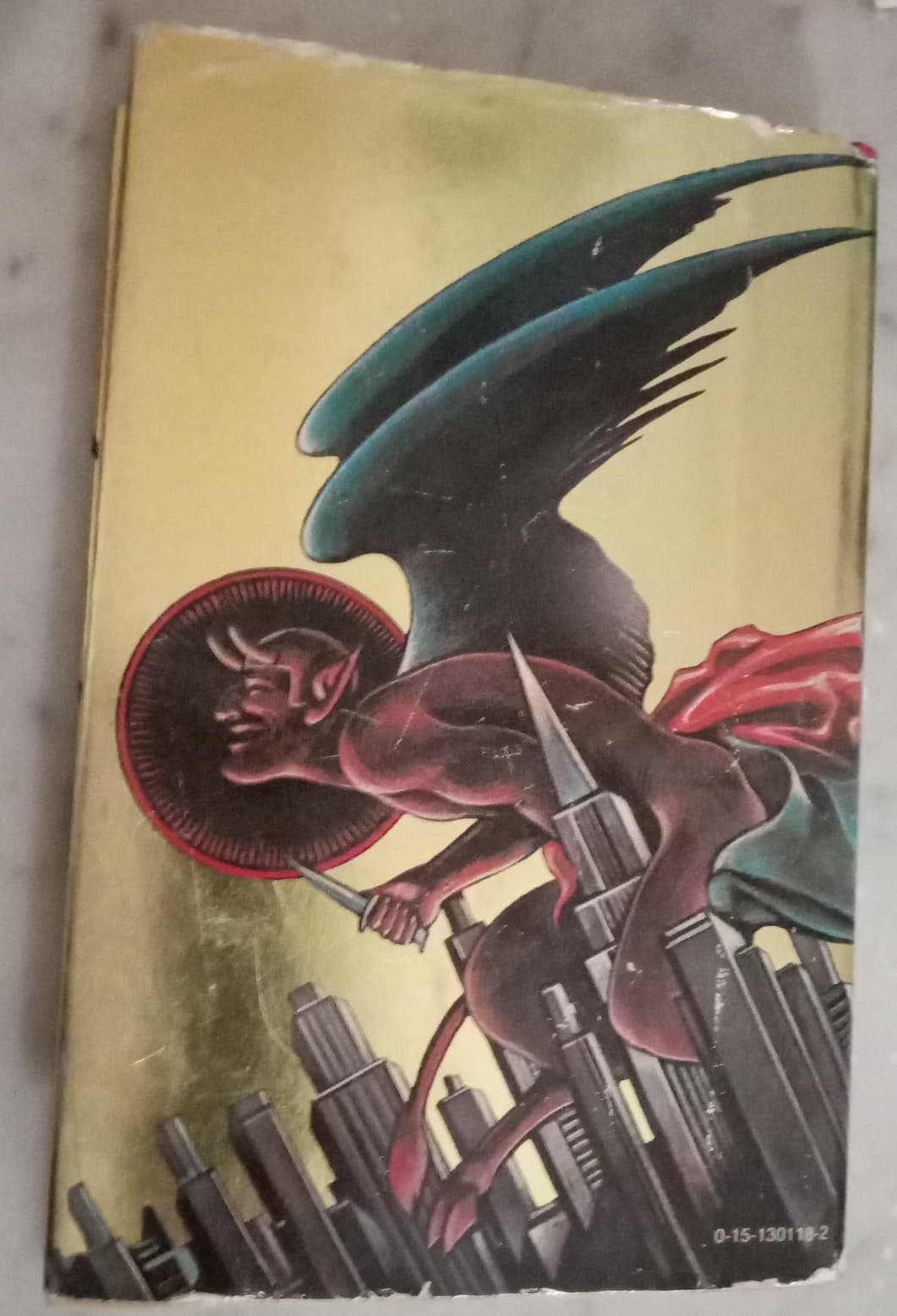

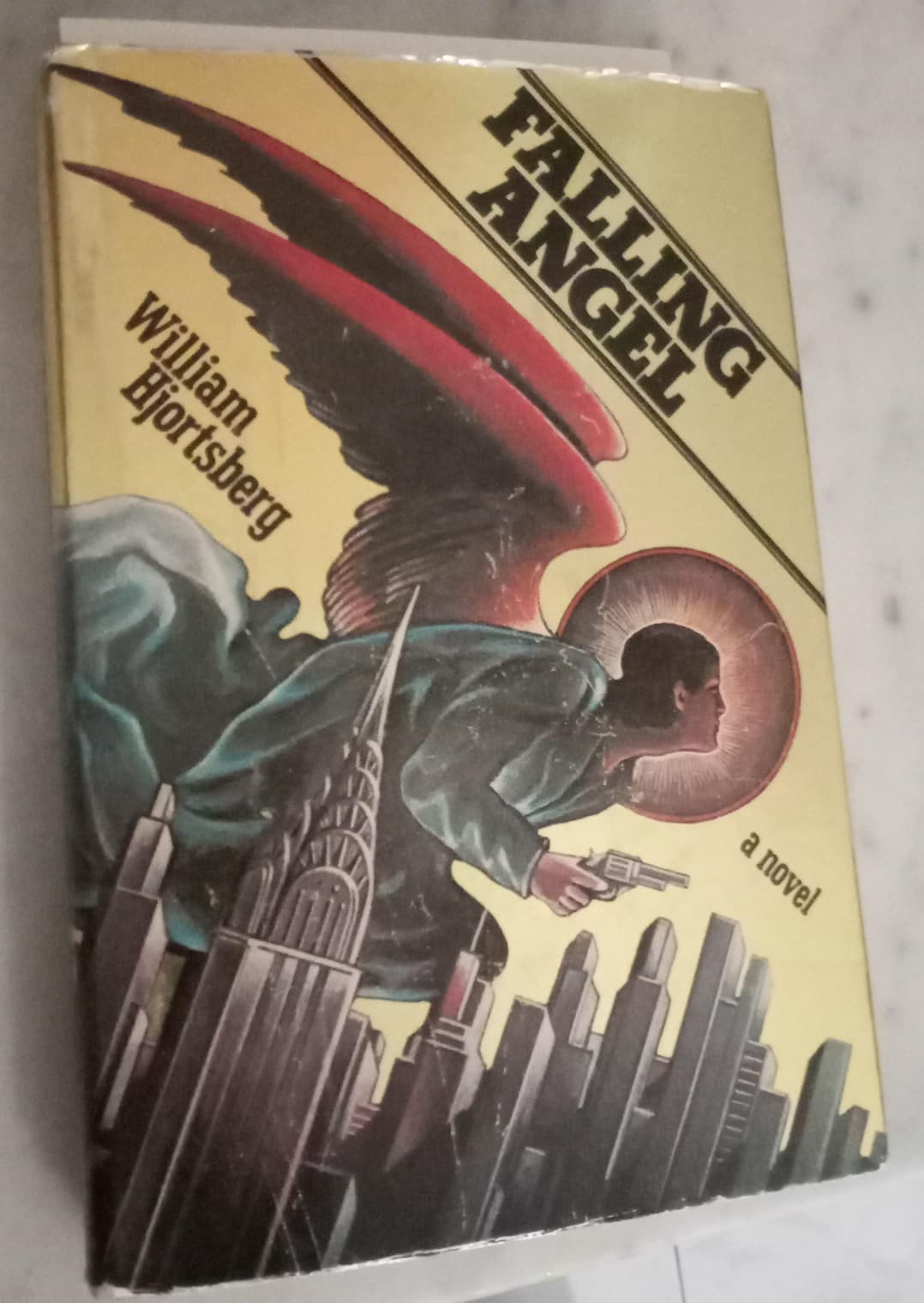

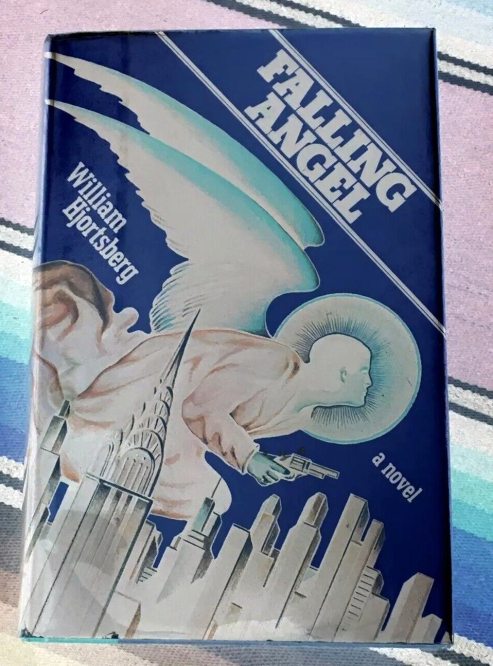

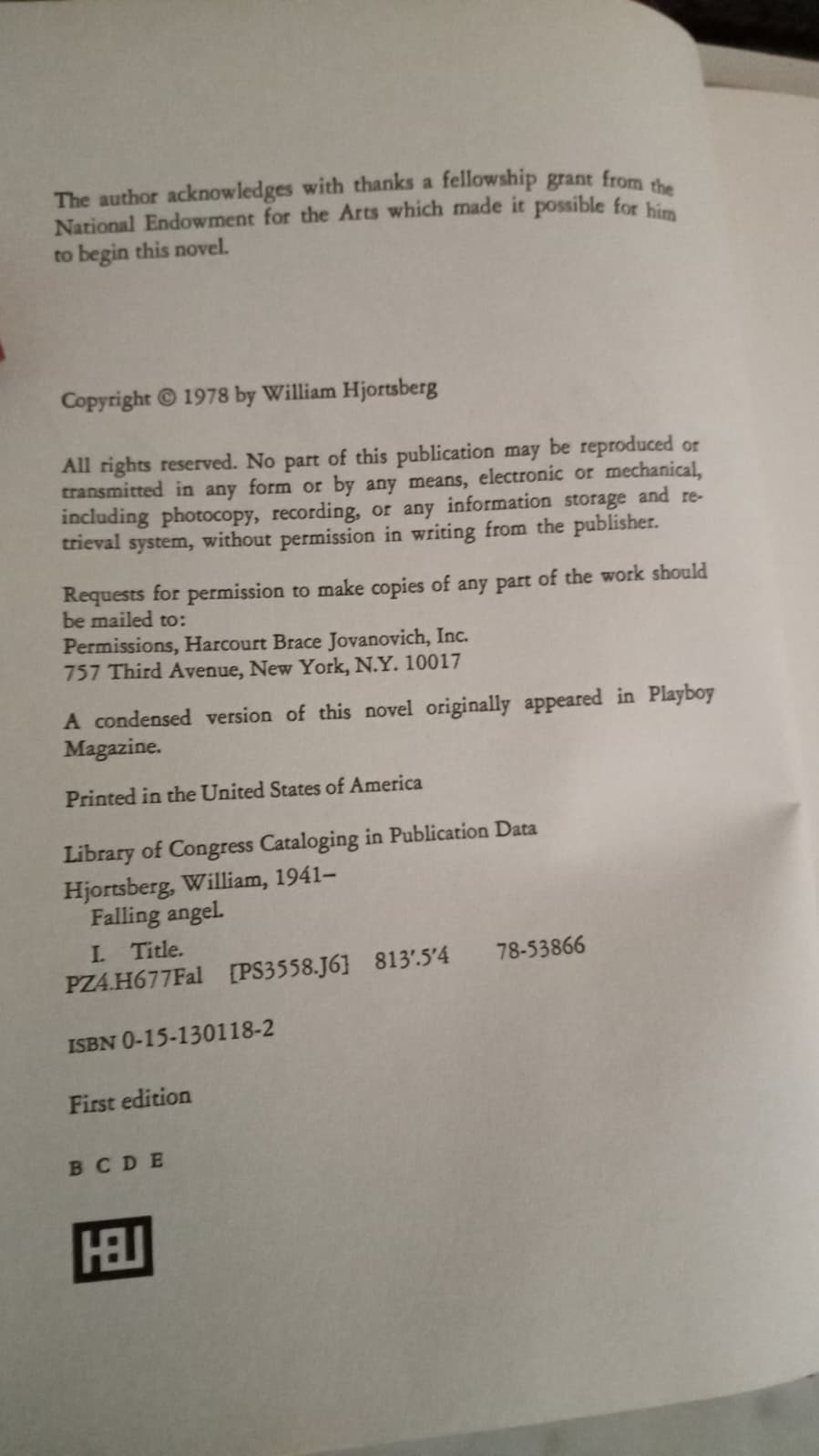

For collectors, the 1979 Book Club Edition hardcover (ISBN 0-15-130118-2) is less prized than the 1978 first edition, fetching $25–$350 based on condition, with signed or near-fine copies at the higher end. Read the book for its cerebral noir; watch the film for its haunting visuals—both will leave you rattled.

As for the value of the first paperback edition for collectors: The first paperback edition was published in 1978 under ISBN 0-15-130118-2 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich / BOMC, has 243 pages, and is in hardcover format.

Based on current listings, used copies in good condition typically range from $200 to around $400, signed much more, depending on wear and any creases or stamps. For near-fine or unread examples, you might see prices pushing $400 or more, though it’s not ultra-rare like some first hardcovers.