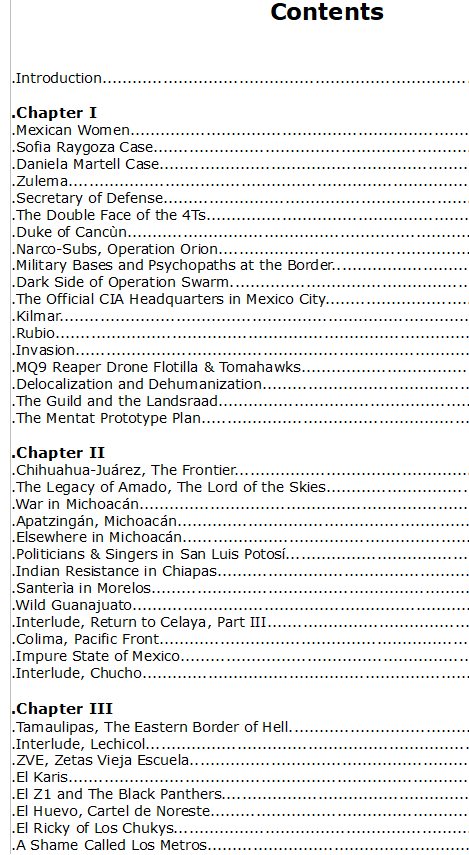

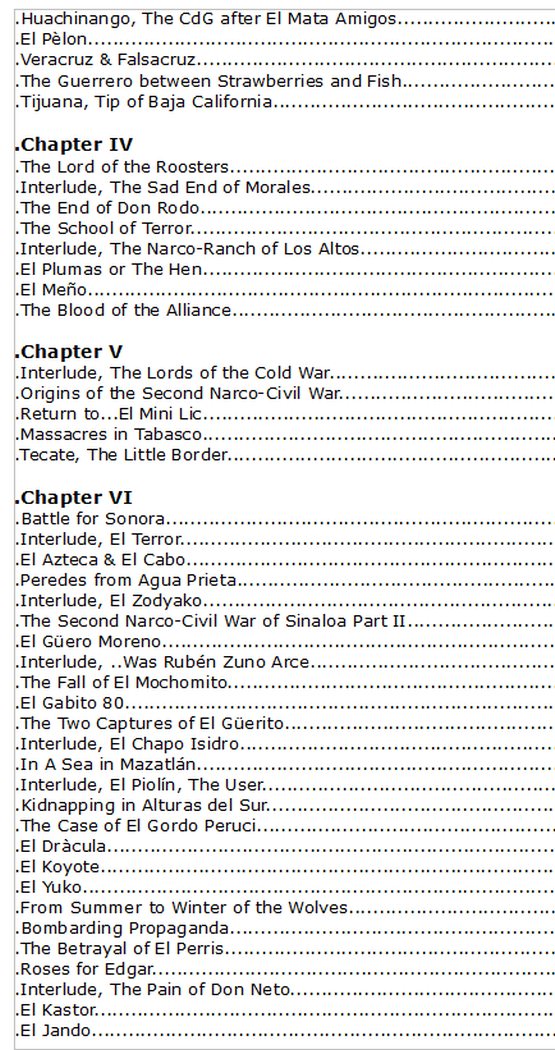

Falsacruz – Mexico’s Hidden Holocaust : A Visionary Blueprint for Ending The Drug War

A seminal critique of Mexico’s protracted struggle against drug cartels, government corruption, foreign interventionism in 2025, and a solution…

Authored by Karl Constantine via Falsacruz-Mexico’s Hidden Holocaust

With Falsacruz, the fourth volume of my books dedicated to the dramatic situation into which Mexico has plunged from the 1980s to today, in addition to describing events and characters in this war that has now taken on all the features of a genocide, I have proposed a feasible solution capable of transforming the narco-economy, which has led to the creation of a shadow Narco-State, into a perfectly legal economy.

If individuals who are attracted to illegal drugs, or who have been involved in them for a long time, were to take nootropic drugs, which are perfectly legal, they would no longer need to ingest dangerous drugs that lead to addiction, delirium, misery, and tragedy. The narco-economy of Mexico and other states, such as Colombia, could then change by developing and producing nootropics capable of providing humans with a rational, constructive, and effective “high.” Not only that. By taking nootropics, those who dropped out of school for various reasons would return to their studies, understanding that not only their own life but also the lives of others are important. Some will weep for the harm they have caused for a long time, and this weeping will be the new growth and rise of a great society in a great country where everyone can live well and in peace through tourism alone-not to mention the development of a perfectly legal agriculture to support biotechnology industries that will arise everywhere.

Beyond this perspective, the book focuses on how this already lost war on drugs has been and still is fought today, highlighting the role-both positive and negative-of the Mexican governments that have succeeded one another over time, and of the DEA, which, no differently from the CIA, instead of always being on the side of legality and protecting innocent civilians, plays dirty, if not very dirty. For example, by controlling the narrative of the narco-war with clandestine blogs managed by its own agents, creating monsters out of scarecrows, fueling the fury of a war that claims hundreds of thousands of victims every year both in Mexico and in the United States. Many will know various internet video platforms dedicated to live-streaming cities like Philadelphia, Chicago, etc., populated by zombie-like humans-poor people addicted to fentanyl-and this terrifying dystopian nightmare is the result of 52 years of drug war waged by the American DEA, an agency that is not only useless but totally harmful and dangerous. To support this claim, I also mention, and add to the previous things, just one name: “Allende.”. Many may find this book utopian, but also disturbing; yet it is reality that compels us authors not only to tell it but also to resolve its deep-rooted problems. As long as the Mexican genocide exists, no one in the West-no matter how well integrated as a productive citizen-can feel at peace or have a clear conscience, because it is foolish to turn a blind eye, thinking these problems do not affect the lives of individuals across the five continents.

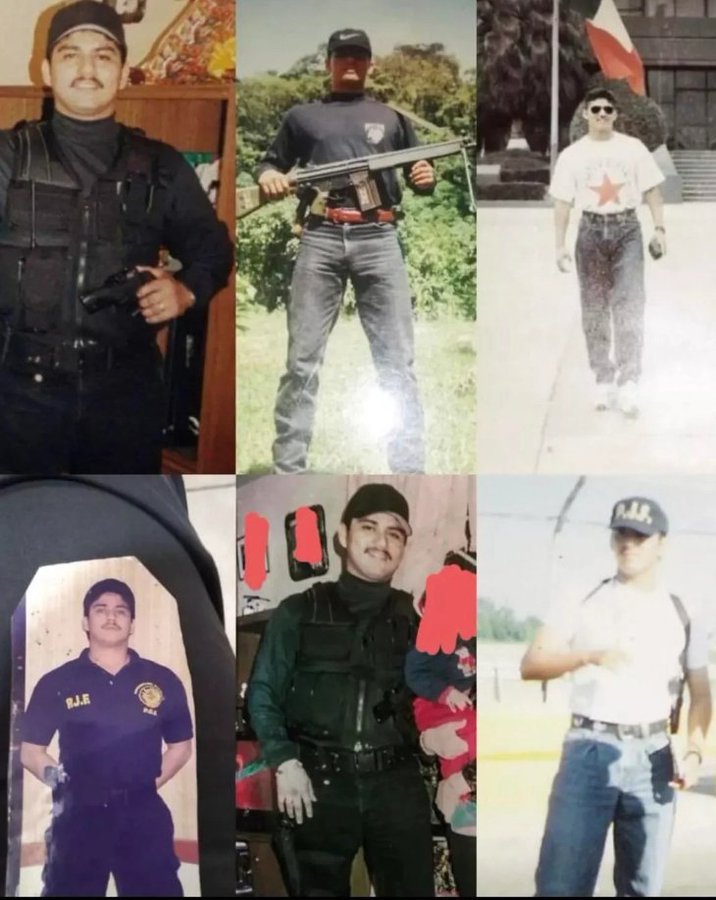

Building on three prior works, Constantine synthesizes decades of research into a searing exposé that diagnoses the systemic failures perpetuating violence while proposing a radical yet pragmatic path toward peace: not the full legalization of the narcotics economy but a radical transformation operated by Biotech-Indutries. This fourth volume distinguishes itself by weaving recent geopolitical developments-such as the clandestine formation of Mexico’s National Operations Unit (UNO), intensified U.S.-Mexico military collaboration, and the collapse of the “hugs, not bullets” doctrine into a cohesive narrative that balances despair with hope. Constantine’s analysis begins by dissecting the shift in cartel strategies since the mid-2000s, when groups transitioned from covert bribery to overt political violence. Drawing parallels to Guillermo Trejo and Sandra Ley’s “criminal governance hypothesis”, the book argues that cartels now function as parallel states, exploiting institutional voids left by corrupt local governments. The 2025 resurgence of clashes in Sinaloa, Jalisco, Tabasco, Guanajuato, and other Mexican states, where cartels retaliated against State crackdowns by burning people and cities, epitomizes this dynamic, revealing how militarized responses, not inadvertently, fuel cycles of retaliation. The author reserves particular scorn for Mexico’s historical reliance on the military to combat cartels, a strategy he links to the 2006 “war on drugs” that displaced corruption from local police to federal forces.

A cornerstone of Falsacruz is its unflinching examination of U.S. culpability. The CIA’s 2025 review of lethal force authorizations against cartels and the deployment of 7th Special Forces Group advisors to train Mexican Marines are framed not as goodwill gestures but as extensions of a century-long pattern of intervention. By dissecting legal precedents like the Posse Comitatus Act’s circumvention, Constantine alleges that Washington’s prioritization of border security over Mexican sovereignty has turned the nation into a “geopolitical laboratory” for hybrid warfare. Indeed U.S. demand for drugs and lax firearm regulations arm cartels with military-grade weaponry, creating a self-sustaining conflict economy.

The book condemns recent U.S. military deployments as violations of the 1945 Chapultepec Peace Accords, arguing that Mexico’s dependency on foreign advisors mirrors the client-state dynamics of Cold War-era Latin America. The military-industrial complex, which has expanded its budget by 300% since 2006, is portrayed as a primary adversary, alongside U.S. agencies reliant on drug war funding. To counter this, the book proposes phased implementation: starting with cannabis and psilocybin to build public trust, followed by nootropics imposition on all levels of the Mexican society. This incremental approach is contrasted with Sheinbaum’s stalled reforms, which prioritized military collaboration over societal buy-in. The book firmly condemns the use of illegality to combat illegality, whether this illegality is expressed through a distorted narrative aimed at covering up the heavy responsibilities of “colleagues,” or through arbitrary arrests, irregular extraditions, and state-sponsored killings.

For scholars and policymakers, the book’s greatest contribution may be its unrelenting emphasis on sovereignty: only by dismantling the illicit economy, Constantine argues, can Mexico escape its status as a pawn in great power rivalries. As cartels experiment with drone warfare and AI-driven logistics, this message carries existential weight.

The road to normalization remains fraught, but as the author reminds us, the alternative-a nation perpetually consumed by someone else’s war-is no longer tenable. In this sense, Falsacruz is less a forecast than a manifesto: a demand that Mexico’s future be determined by its people, not by the whims of cartels or foreign capitals.

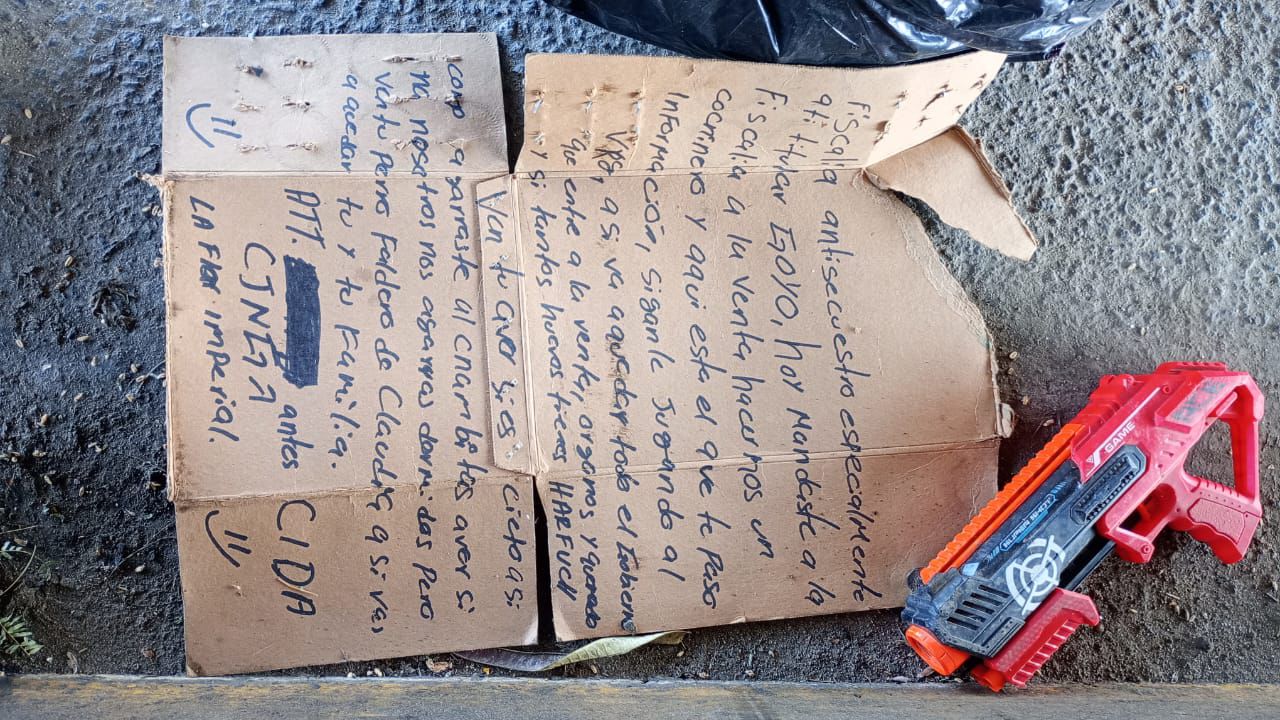

Also the book explores the alliance between Los Chapitos and the CJNG, in the chapter: La Sangre de la Alianza Part II !!!

Available At Amazon

Disponible en español

Disponibile in Italiano