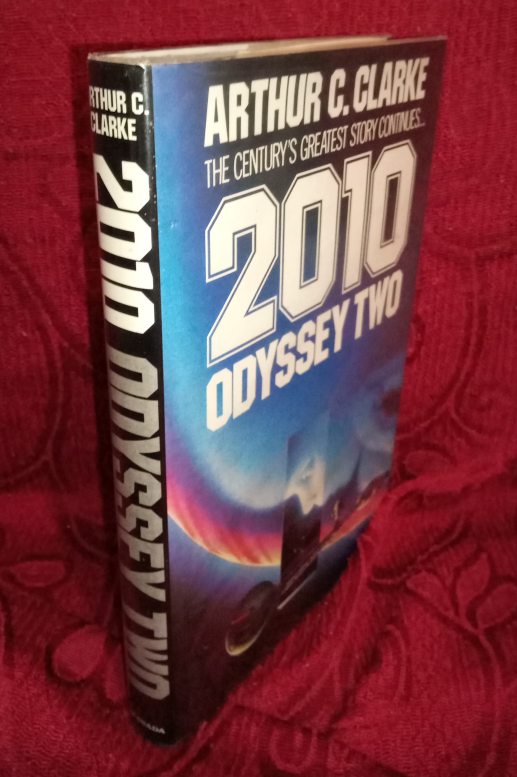

2010, Odyssey Two – Lucifer is Rising

My father bought me this sequel before I read the first Odyssey…

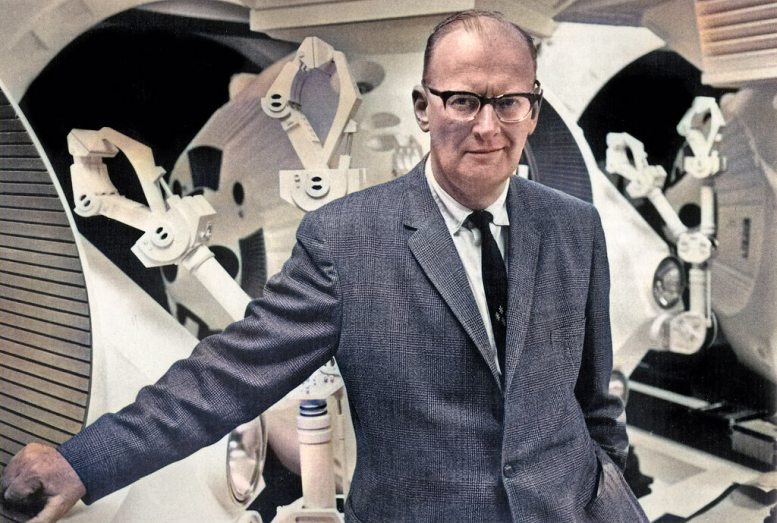

Arthur C. Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two, published in 1982, stands as a remarkable achievement in science fiction literature—a worthy successor to the legendary 2001: A Space Odyssey that manages to answer the burning questions left by its predecessor while creating new mysteries of cosmic proportions. Far from being a mere cash grab sequel, this novel demonstrates Clarke’s continued mastery of hard science fiction and his ability to blend rigorous scientific speculation with profound philosophical themes.

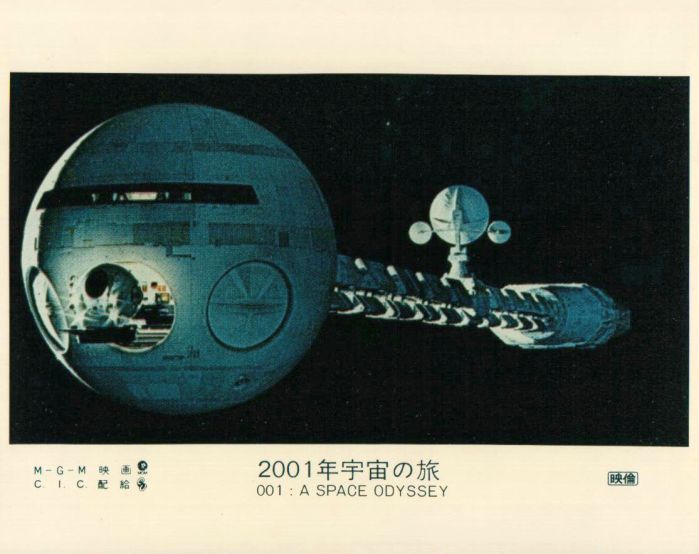

Set nine years after the catastrophic Discovery mission, the novel follows Dr. Heywood Floyd and a joint Soviet-American crew aboard the Russian spacecraft Cosmonaut Alexei Leonov as they journey to Jupiter to investigate the derelict Discovery, the mysterious monolith, and the fate of Dave Bowman. Clarke structures the narrative around multiple objectives: salvaging the Discovery, reactivating HAL 9000, and uncovering the truth behind the alien artifacts that have haunted humanity since their discovery on the Moon.

The story unfolds with Clarke’s characteristic precision and scientific rigor. Unlike the deliberately cryptic nature of 2001, this sequel provides concrete answers while maintaining the sense of wonder that defines Clarke’s best work. The author expertly balances exposition with action, creating a narrative that feels both accessible and intellectually satisfying.

One of the novel’s greatest strengths lies in its character development, particularly compared to its predecessor. Floyd emerges as a fully realized protagonist, haunted by his role in the original mission’s failure and driven by both scientific curiosity and personal guilt. The diverse crew of the Leonov represents Clarke’s optimistic vision of international cooperation, with American and Soviet scientists working together despite Cold War tensions on Earth.

The relationship between the crew members, particularly the growing friendship between the Americans and Russians, serves as a powerful metaphor for humanity’s potential to overcome political divisions when faced with cosmic mysteries. Clarke’s portrayal of this cooperation feels genuine rather than forced, reflecting his belief that space exploration could unite humanity beyond terrestrial conflicts.

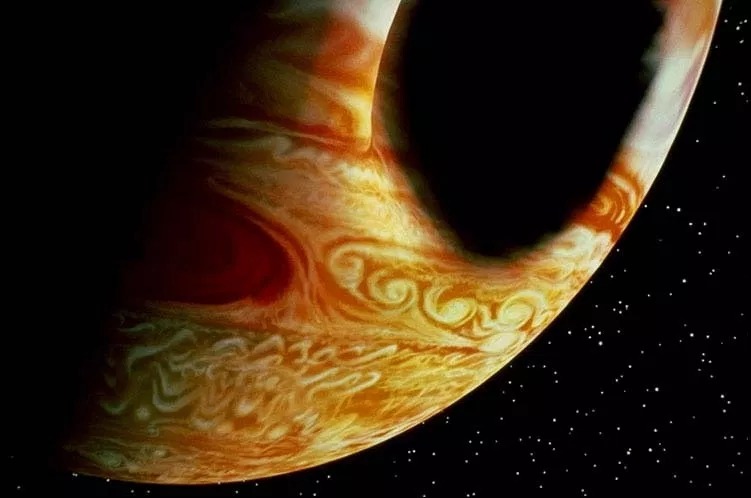

The chapter titled “Lucifer Rising” in Arthur C. Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two describes a pivotal and dramatic event in the story where Jupiter undergoes nuclear fusion and transforms into a small second sun, which is named “Lucifer.” This transformation is caused by a vast population of self-replicating monoliths that increase Jupiter’s density until fusion ignites. The creation of this new sun illuminates the solar system in a new way, effectively banishing darkness. Clarke envisions this event metaphorically as the bringing of light—akin to the figure of Lucifer as “light-bearer”—and it has profound effects on humanity and the solar system’s lifeforms. The illumination leads to the disappearance of night, fear, suspicion, and many crimes of the dark. This final section of the novel emphasizes humanity’s metaphorical and literal “illumination” through the light of this new star, expanding on philosophical and symbolic themes about light and darkness.

Clarke’s reputation for scientific accuracy shines throughout the novel. His descriptions of Jupiter’s moons, particularly Europa, demonstrate remarkable prescience—many of his speculations about the Jovian system have proven surprisingly accurate in light of subsequent space missions. The author’s background in physics and his involvement with space exploration organizations lend authentic weight to his technical descriptions.

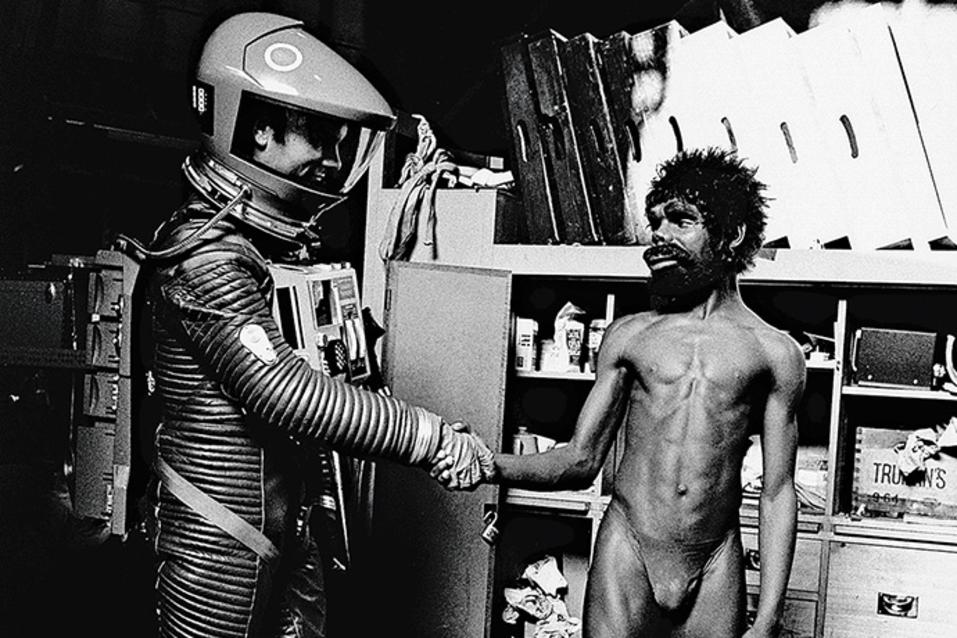

The novel’s exploration of artificial intelligence through HAL 9000’s rehabilitation provides both emotional depth and philosophical inquiry into the nature of consciousness and redemption.

Dr. Chandra’s efforts to understand and repair HAL create some of the book’s most compelling scenes, blending technical detail with genuine emotional resonance. Clarke’s prose remains characteristically clear and elegant, avoiding the purple prose that can mar lesser science fiction while maintaining the poetic sensibility that elevates the best genre writing. His ability to convey complex scientific concepts in accessible language serves the story well, never allowing technical exposition to overwhelm the narrative drive. The novel’s pacing proves superior to its predecessor, maintaining momentum while allowing for the detailed exploration of ideas. Clarke successfully balances multiple plot threads—the mission to Jupiter, the investigation of the monolith, Bowman’s transformation, and the growing tensions on Earth—without losing narrative focus.

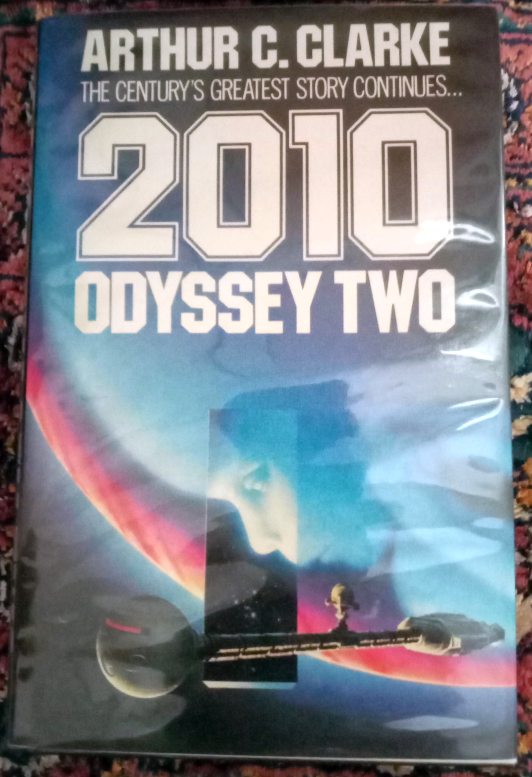

First UK Edition Value and Bibliographic Details

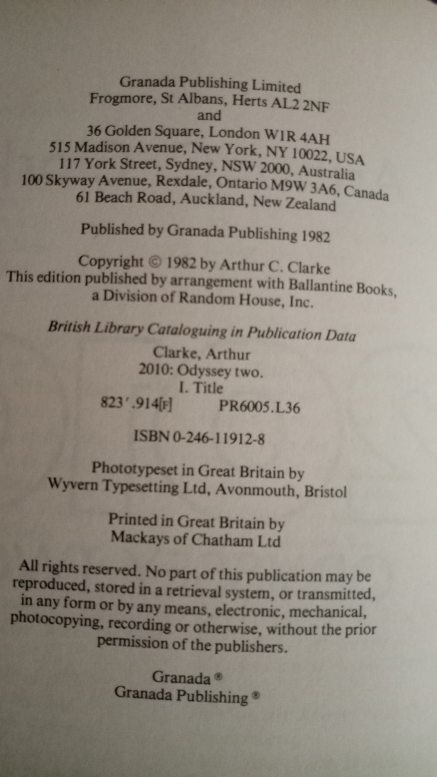

The first UK edition of 2010: Odyssey Two, published by Granada Publishing in 1982, represents a fascinating case study in bibliographic complexity. The edition exists in multiple states, with the most intriguing being the first state copies where the author’s name was misspelled on the title page. According to collectible book specialists, some early copies of the first UK printing featured “Clarke, Arthur C.” in an incorrect format or with spelling errors, leading to these copies being withdrawn and corrected.

The corrected later state copies, which feature the author’s name spelled properly as “Arthur C. Clarke” on both the title page and copyright page, are now considered more desirable by collectors. First edition copies in fine condition with unclipped dust jackets typically command prices ranging from £50-100 for good copies, with signed editions reaching £200-300 or more, but soon things will change. This book value is destined to grow.

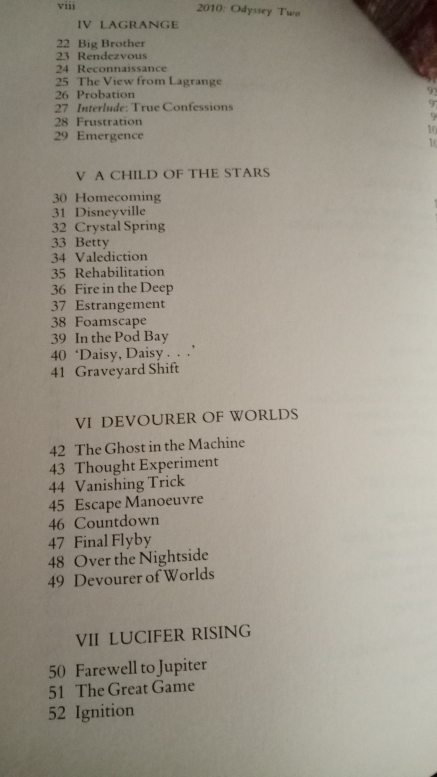

The first UK edition can be identified by several key points:

– Published by Granada Publishing, 1982

– ISBN: 0246119128 (hardcover)

– Later state copies have “Clarke” spelled correctly throughout

– Original price-unclipped dust wrapper is essential for value

– 216 pages in the UK edition versus 291 in the US edition

Cover Art and Design

The cover art for 2010: Odyssey Two was created by Michael Whelan, one of science fiction’s most celebrated artists. When legendary publisher Judy-Lynn del Rey commissioned the cover, she specifically requested a “big book look” that would appeal to mainstream bestseller audiences. Whelan responded with one of his most memorable pieces, utilizing an almost exclusively airbrush technique to achieve a distinctive diffuse, soft-edged aesthetic that perfectly captured the cosmic scope of Clarke’s vision. The artwork depicts the mysterious monolith against the backdrop of Jupiter and its moons, rendered in Whelan’s characteristic style that balances realistic detail with dreamlike atmosphere. The jacket design by Gary Friedman complements Whelan’s artwork perfectly, creating a visual presentation that has become iconic in science fiction publishing. This cover art significantly contributed to the book’s commercial success and remains one of Whelan’s most recognizable works.

Several fascinating details surround the publication of 2010: Odyssey Two:

The Name Spelling Issue: The most significant curiosity involves, as said, the author’s name presentation on early UK first edition copies. Some initial printings featured formatting errors where “Clarke, Arthur C.” appeared instead of the standard “Arthur C. Clarke,” leading to these copies being withdrawn and corrected. This created distinct “states” within the first edition, making bibliographic identification crucial for collectors.

Movie vs. Book Continuity: Clarke made the unusual decision to base his sequel on Kubrick’s film rather than his own novel, changing the setting from Saturn (as in the original book) to Jupiter (as in the movie). This choice created some continuity issues but allowed Clarke to incorporate new scientific discoveries about Jupiter made by the Voyager probes in the late 1970s.

The Tsien Subplot: One of the novel’s most compelling elements—the doomed Chinese expedition to Europa—was completely omitted from the 1984 film adaptation. This subplot, which Clarke described as having elements of cosmic horror, features the Chinese spacecraft Tsien being destroyed by indigenous Europan life forms, leaving only one survivor to radio a final message.

Scientific Prescience: Many of Clarke’s speculations about Jupiter’s moons, particularly Europa’s subsurface ocean and potential for life, have proven remarkably accurate in light of subsequent space missions. His descriptions of the Jovian system written in 1982 align surprisingly well with discoveries made by later space probes. Regarding the impact of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, which famously collided with Jupiter in 1994, creating massive observable explosions in the planet’s atmosphere, this real event occurred after Clarke’s 2010 was published (1982). Clarke’s novel, however, prophetically centers on a dramatic transformation of Jupiter when monoliths cause the planet to ignite into a second sun, called Lucifer. While Clarke did not predict the comet impact itself, the general idea of Jupiter undergoing profound changes or cosmic events was creatively anticipated by his story.

Cold War Context: Written during the height of the Cold War, the novel’s optimistic portrayal of Soviet-American cooperation in space reflected Clarke’s belief that cosmic perspectives could transcend earthly conflicts. The book’s dedication to both cosmonaut Alexei Leonov and dissident scientist Andrei Sakharov demonstrates Clarke’s nuanced understanding of Soviet society.

Clarke demonstrates that it is possible to provide answers to cosmic mysteries without diminishing their wonder, creating a novel that satisfies curiosity while inspiring new questions about humanity’s place in the universe. The book’s combination of hard science, philosophical depth, and genuine human emotion creates a reading experience that honors its predecessor while charting new territory.